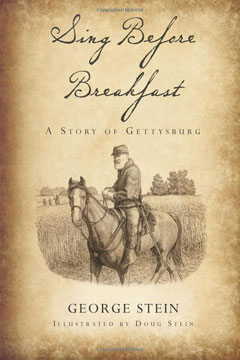

Sing Before Breakfast

A Story of the American Civil War

by George Stein

illustrated by Doug Stein

|

| |

| Now on sale, at Amazon.com | ||

Sing Before Breakfast is a book that traces cataclysmic changes in the national character of the United States during the Civil War through the epiphany of a twelve-year old farm boy, Reis Bramble. This is an account of his experience written in the weeks subsequent to the Battle of Gettysburg from notes taken during three days of terror. He refines his story over the years with the small enlightenments that come with time.

He and his horse and dog are caught between the lines on the first of three days of battle. With no safe way home, he takes refuge with the Union army and, because of his knowledge of local streams, roads and land features, is asked by General Meade to serve as a “scout” during the army’s tenure at Gettysburg. He is thrilled to accept but finds that the glamour of war is soon replaced with the brutal horror and extreme violence of the battlefield.

He observes that in peacetime, anyone who commits violence faces retribution, but that in time of war, such behavior is applauded and decorated. He tries to reconcile his Christian upbringing and the tenets of the “Good Book” with what he sees good Christian men do to other good Christian men. In this he fails. Although he too is caught up in and succumbs briefly to the ancient lure of the battlefield, he concludes that war is the wrong answer for resolving irreconcilable differences between people.

Nonetheless, the first three days of July 1863 change him forever:

EXCERPTS:

“We were all as innocent as newborn lambs here in Adams County before the rebel army came through. We thought we knew all about war, but we knew next to nothing, and when it came, it came down on us hard. Before that, my world was a place where everyone … lived by a principle that friendliness, cleanliness, hard work and prayer would meet the needs of the day and keep us on course for eternal life.

“The land and its treasures were our livelihood and our welfare, and our elders demonstrated respect and reverence for all of it. We exploited the land but respected it as if it were on loan from God. We were taught to make use of animals sparingly and with love and compassion. Pa allowed as how there was no nobler profession than for one to make his living from the earth and that God smiled with favor on the ‘husbandman.’ The magic of the seed, the soil and the seasons were God’s other gifts and man was the instrument by which the whole was wrought.”

* * *

“Boy, what the hell you doin’ around here?” I shrugged and flapped my gums a bit, but nary a sound came out. It was the best I could come up with, beings I felt so outnumbered. His steel-blue eyes pierced me from under the visor of his forage cap. I sat and squirmed, then tried to be nice and appeal to his vanity.

“What’s life in the cavalry like?” I asked pleasantly.

“A long stretch o’ nothin’ and a whole lotta horseshit!” He turned aside in the saddle and spit down from his chaw. “Now git on out of here. This here’s no place for you now!”

* * *

The three rebels were all young, lean, shabby, hairy, bearded and filthy. One had no shoes, and the other two weren’t much better off. All had tattered hats of different description, which they had removed when they gathered around the officer. Their muskets were ominous and worn smooth and burnished from long use. They stacked them in a corner of the room along with their cloth haversacks, canteens, knapsacks, blanket rolls, ammunition pouches and bayonets. I tried hard to keep from staring at the muskets and bayonets. All three men wore simple tattered shirts and trousers of homespun. One man carried a long-barreled revolver tucked into a rope about his waist, and stood facing toward the window a bit where he could keep an eye on the approach to the front door. Other than that, there wasn’t a whit of difference between them.

* * *

There is a particular air about generals that sets them apart. In their presence, lesser officers tend to be fidgety and nervous, whereas the generals never are. They have achieved a lofty place, a club, an exclusivity. I read somewhere about a king who had this fellow whose job it was to follow him around with a chair. Whenever the king felt ready to sit down, he simply did so without looking back, confident that the chair would be there. Generals are something like that, particularly the ones with two stars. They stand central and look yonder, while those of lesser rank hover at the edges and are quick to cater to their orders and demands. Generals have a look, a posture, a commanding presence about them, and you’d know they were generals even without their stars and buttons.

* * *

“I missed my home and my bed … and somehow most of all right now, my gentle and familiar chickens. I tried to hold down a big lump deep in my throat that was trying hard to work its way out. I awoke and stared up into the night and felt as far from home as if I was one of those distant stars, all alone away up there in some way off corner of the sky.

“I reached over and hugged Old Jack just to bring me back down to earth. He answered with a reassuring flap, flap of his tail.”

* * *

Some were too severely injured to move. In this long night of agony, most went without food or water. Great rains would come late tomorrow and continue for days. Many of those left behind would lie undiscovered and helpless in the mud. Others would pass from this earth quietly and alone in the night. Haunting cries for water arose from all parts of the field near and far like strange and doleful birds of night. Poor horses whinnied most pitifully and struggled to rise on legs no longer there.

But for now, in this night, the bands have stopped, and there is silence at last. You can close your eyes and make yourself believe that nothing happened here – except for this telltale silence: no whip-poor-wills, no tree frogs, no screech owls, even the silent fireflies are gone.

And in the morning, there will be no birds, no dogs, no roosters, no bleating sheep, no cowbells in the meadow, only pistol shots for wounded horses and the incessant hum of billions of blowflies.

* * *

The momentum of the battle now drew me into it. I bit open a cartridge, poured in the powder, rammed in the ball, pulled back the hammer and set the cap. I laid the musket across the rock, pulled the hammer to full cock and pointed it at the approaching enemy. I closed my eyes, and suddenly the gun fired. I don’t know if my finger had been tightening of its own accord or whether I simply had come to the edge of conclusion and was disposed to act. I opened my eyes, and as the smoke parted, a young rebel I had noticed was gone. The possibility that his disappearance was because of what I had just done filled me with remorse.

* * *

“I’m not young anymore, “said Lieutenant Haskell. “I’m at an age that’s like when you throw a ball straight up in the air, and it hangs there a moment before it starts back down. When you’re young, everything goes upwards. Then it slows down a little, and you reach forty and life hangs there a bit before starting downwards. It’s a wonderful time, a time of maturity and a time before old age makes itself known, a time when all your memories are still of youth. Then the ball begins to fall. It’s called dying.”

* * *

Some corpses were found as long as months later, in haystacks, in hay mows, in dark corners of barns and cellars, wherever they had crawled to nurse their wounds and die, alone, unknown, missing … missing from loved ones, missing from life. Other corpses had been rooted up and eaten by hogs or torn apart by dogs … somebody’s son, somebody’s brother … somebody’s husband or father, somebody’s handsome little boy.

* * *

“I felt bursts of exhilaration come and go that the thing was over. I was stronger for the experience. Not happy, but stronger. The enormity of it changed us all forever. Gone was a kind of trust that life was full of good and that good people had little to fear. There comes a time when such innocence must go out and meet life firsthand, perhaps too soon for every pitfall to be foreseen, but at a time when instincts for survival must serve you quickly. If you pass through and survive, by and by you may feel something of your old self coming back but with a new layer added to your character.”

* * *

The rebel grabbed Sport’s saddle horn and was fixing to mount up when I grabbed at his pants and pulled for all I was worth. Old Jack joined in and was barking and biting at the rebel’s bare feet. He kicked at Old Jack and gave me a backhand that sent me sprawling. I got to my feet and grabbed at him again. I tried desperately to get the pistol Lieutenant Haskell had given me out of my pocket but caught the hammer in the rope that served as my belt. I hadn’t even checked to see if it was loaded. He knocked me down again, and, this time, he sat astride me and held one of those rebel short swords over me. I reached up and grabbed his wrist, but he was too strong, and I couldn’t hold him back.

* * *

Almost home, Reis meets up with old Bum Piles who tells him, “You’re the one that makes life what it is … there ain't no secret, and there ain't no magic God gives you later that you don't have inside you right now. But find it before you let your lifetime pass by … one of the biggest mistakes you can make with y’self…maybe the onnee real one…is to let life get away from you. Then you wake up old, like me, and wonder who you are and wonder who you was.

“Don’t pay no mind to what ever’body else thinks, Reisie. Find out y’self. Them that thinks they knows it all has stopped learnin’. Don’t worry if you don’t understand ever’ little thing just yet. Leave a little room for faith and magic. As for religion, beware o’ them that says their way is the onnee way. God is a mystery. Do whatever puts God in your heart, and all will come right. Don’t fret about all the rest.”

* * *

“I guess, for a long time, I had lost my trust in most grown up people. I neither trusted what they said nor what they said they believed anymore. In time, I came to a gentler conclusion: that most people are not inherently mean, or evil, or stupid, but that each and all alike contend with life as they see it and as best they can – and are, after all, as all of us are, only pilgrims headed home.”

“I guess, for a long time, I had lost my trust in most grown up people. I neither trusted what they said nor what they said they believed anymore. In time, I came to a gentler conclusion: that most people are not inherently mean, or evil, or stupid, but that each and all alike contend with life as they see it and as best they can – and are, after all, as all of us are, only pilgrims headed home.”